In the latter 17th Century — the late 1600s — there was a significant change in Russian icon painting. That was an important century, historically.

First, in its middle, came the huge controversy in the Russian Orthodox Church over revisions in ritual (such as how to make the sign of the cross) and in liturgical books. Patriarch Nikon, the head of the Church, thought that the way the Greeks did things at that time was the correct model to follow, and that the Russian Church had deviated from what he thought was that standard. On the other hand, conservative traditionalists were furious over that uppity Nikon wanting to change the way their fathers and grandfathers and great-grandfathers had done things, and saw Nikon as a dangerous heretic. How dare he say that the spelling of Jesus should have an extra letter! How dare he change the way everyone had always crossed themselves, saying that the fingers had to be in the position used by those deviant Greeks, who, after all, had their civilization destroyed for their evil ways when God punished them for their heresies by allowing the Moslems to conquer Constantinople, the Second Rome, in 1453!

Well, Moscow was now the Third Rome, the bastion of true Orthodoxy, the conservatives believed — and now that devilish Nikon was trying to lead the Russians away from the true path! They were having none of it, and their chief spokesman, the Archpriest Avvakum, ranted against the innovations of Nikon and eventually got himself murdered for it by the authorities as a consequence.

In short, there was a tremendous schism in the Russian Orthodox Church, and it separated into two main divisions: first, that of the conservatives who firmly maintained the old ways of doing things, and second, that of the State Church, with the punishing authority of the Tsar behind it. As a consequence, the Old Believers — the “Old Ritualists” went one way, and the State Church, persecuting those they considered to be raskolniki — “schismatics” went another.

For a short time this had little effect on icon painting. Nikon, after all, did not like Western European religious painting any more than did the Old Believers. Nonetheless, even in his time the influence of the “Franks,” meaning the Western Europeans such as Germans, Dutch, and Italians — penetrated first secular painting, and soon after, icon painting.

Just as the Russians liked to say, for appearances, that icons were “exchanged” instead of “bought,” even so the moderates who wrote of icon painting at that time were perfectly willing to allow such new “Frankish” innovations into icons as naturalistic shading and perspective, while maintaining that all was still perfectly “Orthodox” as long as such painting maintained the podobie, the “likeness” of Jesus and Mary and the saints. But that “likeness” was understood very loosely, so loosely in fact that it was little more than the general outline of a saint or type.

This was, after all, the period when the Russians began to really look to the West, realizing that it was making rapid strides in many fields while Russia was still lingering in the Dark Ages. And when Peter I — Peter the Great as he is called — came to power, he had little patience with Russian “overkill” in the matter of icons. He was quite aware that the Westerners in Russia at that time looked on the over-the-top veneration of icons they witnessed in Russian churches and public and private buildings as backward idolatry, so Peter took steps such as clearing out the numerous icons found on Russian ships, reducing the allowed number to one only; he is said to have done the same in his own residences, getting rid of all the numerous icons of saints and keeping only the cross and an icon of Jesus. He also tried — not entirely successfully — to stem the Russian predilection for declaring icons “miracle-working.”

A good marker for the change in art in the latter part of the 1600s is the painter Simon Ushakov, who maintained the old forms of icons while nonetheless incorporating shading and perspective. No longer were all icons to be rigidly stylized; instead, lines softened, garments began to drape naturally, the use of more accurate light and shadow was introduced, and a more naturalistic way of depiction in general became the norm.

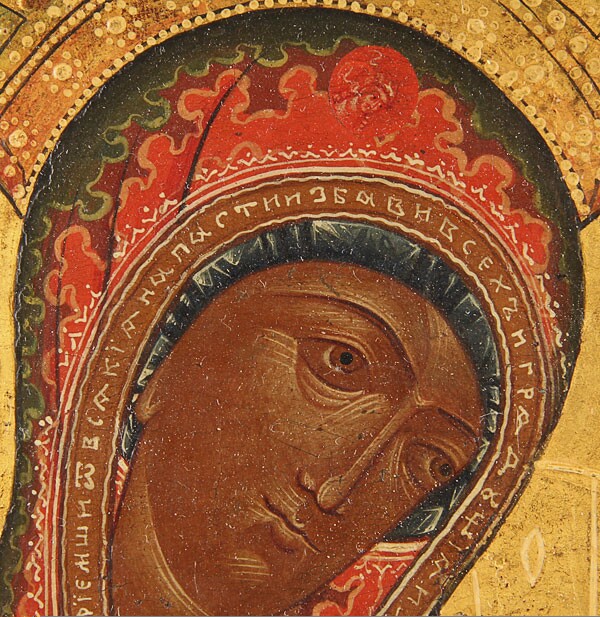

We can see this “having it both ways” mode of icon painting quite clearly in Ushakov’s version of the Kykkos Mother of God — his rendering of a supposedly miraculous Greek icon of Mary and the child Jesus. Here it is:

There are a number of things to note about this painting. We can see first of all, that there is a conscious effort to make the figures more real and naturalistic; they have not only more realistic proportions than in traditional icon painting, but also attention is paid to correct shading and there is a move toward natural draping of the garments, though there is still some stylization in the folds. Coloring — such as that of the flesh — is far more realistic.

I would like you to look at it very closely, particularly at the eyes (see the detail image below). In them you will find a useful tip for dating. I once saw an icon of the Georgian (Gruzinskaya) Mother of God type in a university museum, and I could tell immediately that the date on its label was considerably earlier than it should have been. How did I know? Because the inner corner of the eye had that little dot of flesh (technically the lacrimal caruncle) that eyes really have, and that we see in the inner corners of the eyes of Mary in Ushakov’s Kykkos icon. That little detail is not found in Russian icons before the latter part of the 1600s.

Nonetheless, even with the advent of greater realism, State Church icons in Russia retained an inherent conservatism of form. Ushakov’s painting of the Kykkos Mother of God is still rather rigid, and painters tended not to adapt the more relaxed attitude toward positioning figures that was found in Western European religious art of the period. Ushakov is, in a sense, still “copying,” still keeping the podobie — the “likeness” or “form” — while filling that form with greater, though still restrained, naturalism.

Of course that does not mean the old stylized manner was abandoned in Russia; it was kept alive by the Old Believers, who continue to paint stylized icons right up to the present. In the following example, though considerably later than Ushakov, we find the figures depicted as though the innovations of Ushakov and those like him had never taken place:

Ushakov also reflects his conservative side in the inscription on the Kykkos image, which shows its Greek title — written in Greek:

It reads “HE ELOUSA HE KYKYOTISSA — literally “The Merciful the Kykkos” (Meaning “The Merciful One of Kykkos”). But in very small, nearly invisible letters just below ELEOUSA is written its translation in Church Slavic: Milostivaya — meaning “Merciful” — a tiny concession to those who wanted things more “Russian.”

Similarly, Ushakov has given the scroll text held by the child Jesus (the beginning of Luke 4:18-19) in Greek:

Πνεῦμα κυρίου ἐπ’ ἐμέ, οὗ εἵνεκεν ἔχρισέν με [εὐαγγελίσασθαι πτωχοῖς, ἀπέσταλκέν με κηρύξαι αἰχμαλώτοις ἄφεσιν καὶ τυφλοῖς ἀνάβλεψιν, ἀποστεῖλαι τεθραυσμένους ἐν ἀφέσει, κηρύξαι ἐνιαυτὸν κυρίου δεκτόν.]

Just above it, however, is written the translation of the text in Slavic.

Дух Господень на Мне: Егоже ради помаза Мя [благовестити нищым, посла Мя изцелити сокрушенныя сердцем, проповедати плененным отпущение и слепым прозрение, отпустити сокрушенныя во отраду, проповедати лето Господне приятно].

“The Spirit of the Lord is upon me, because he has anointed me [to preach the gospel to the poor; he has sent me to heal the brokenhearted, to preach deliverance to the captives, and recovering of sight to the blind, to set at liberty them that are bruised, To preach the acceptable year of the Lord].”

We find a date and painter inscription to the lower right of the scroll. The signature reads: писал Пимин Феодоров зовом Симон Оушаков

“Painted by Pimen Feodorov, called Simon Ushakov.”

But what of the original Kykkos image?

Well, as you know by now, all of these famous icons — famous because they are considered to be miracle-working in the Eastern Orthodox branch of Christianity — have their various origin stories, and the Kykkos icon (that is a simple name for it in English) is no exception.

You will recall that one way to give great importance to an icon was to say it was painted by St. Luke. In a previous posting I discussed the fact that there is no support whatsoever for the notion that a St. Luke ever painted icons in the first years of Christianity, and that quite to the contrary, the first Christians did not paint or venerate icons, and would have considered the whole notion frightfully pagan.

And speaking of pagan notions, that is one of the most interesting things about the Kykkiotissa icon.

There is the motif in ancient Greek mythology of the “person that must not be looked upon.” It has its variations. There is, for example, the Gorgon Medusa, whose countenance was so frightful that anyone who looked upon her would be turned to stone. And there is the tale of Semele, the unfortunate girl who wheedled the promise from Zeus that he would grant her a favor, and then asked to see him in all his full splendor. Well, you may recall that when Semele saw him in his glory, she was consumed to ashes.

A variation on that motif is applied, oddly enough, to the Kykkiotissa icon, which is kept in the Kykkos Monastery on the island of Cyprus. Unlike most such icons, the faces of Mary and the child Jesus on the Kykkos icon are not to be seen, but are always covered with a veil that obscures a good part of the image. That is because it is generally believed that to look upon the faces of that icon will bring misfortune — even blindness — to the viewer. This does not generally apply to copies of the image, in which there is no such prohibition.

The origin story of the icon relates that it was sent by Luke to Egypt. When persecution arose there, the icon was packed off to the chief city of the Byzantine Empire, Constantinople, in the year 980. There was a delay when the ship was attacked by Saracens, but eventually the icon made it to the great city. Keep in mind that these tales are hagiography (not reliable history) — religious writings for what we today would call propagandistic purposes.

The icon was then said to have been sent by the Byzantine Emperor Alexios I Komnenos to Cyprus in 1082, after the Emperor’s daughter became inexplicably ill. The Emperor was told that she would be cured if he would send the miraculous icon of Mary to the hermit Isaiah on Cyprus, who had been having divine revelations that Mary wanted her image there. Isaiah built a church to house the image, and when the Emperor finally did send it, it was placed in the new church.

As is frequent in such stories, there are little details such as the Emperor’s hesitation after agreeing to send the image, during which he was punished by heaven for not getting on with it, but again as usual, all was made right when he did finally send it to Cyprus. Monks settled around the church, an abbot was appointed, and the monks were given land and three villages. And that was the origin of the Kykkos monastery.

We find the usual miracle stories associated with the Kykkos image — cures of physical ailments, prayers for rain answered, and also the usual “negative side” miracles, such as the withering of the hand of someone who showed disrespect to the icon.

Copies of the Kykkiotissa image began being painted in Russia in the 1600s, which is why we find the type among the extant icons painted by Simon Ushakov. The Russians generally call it the Milostivaya Kikkskaya — the “Merciful Kykkos” icon.